Last month, we celebrated Black History Month.

I believe that Black History Month happens every month for me as I think about the shoulders that I stand on to engage in the work at the intersection of racial equity, inclusion and the outdoors.

As the “official” month of Black History was underway, I found myself thinking about my grandmother who turned 102 on February 13th. She remembers what she wants to remember, walks with the aid of a walker and loves red roses. When I share my work with her, she is excited that it involves connecting Black people (& others) to the outdoors.

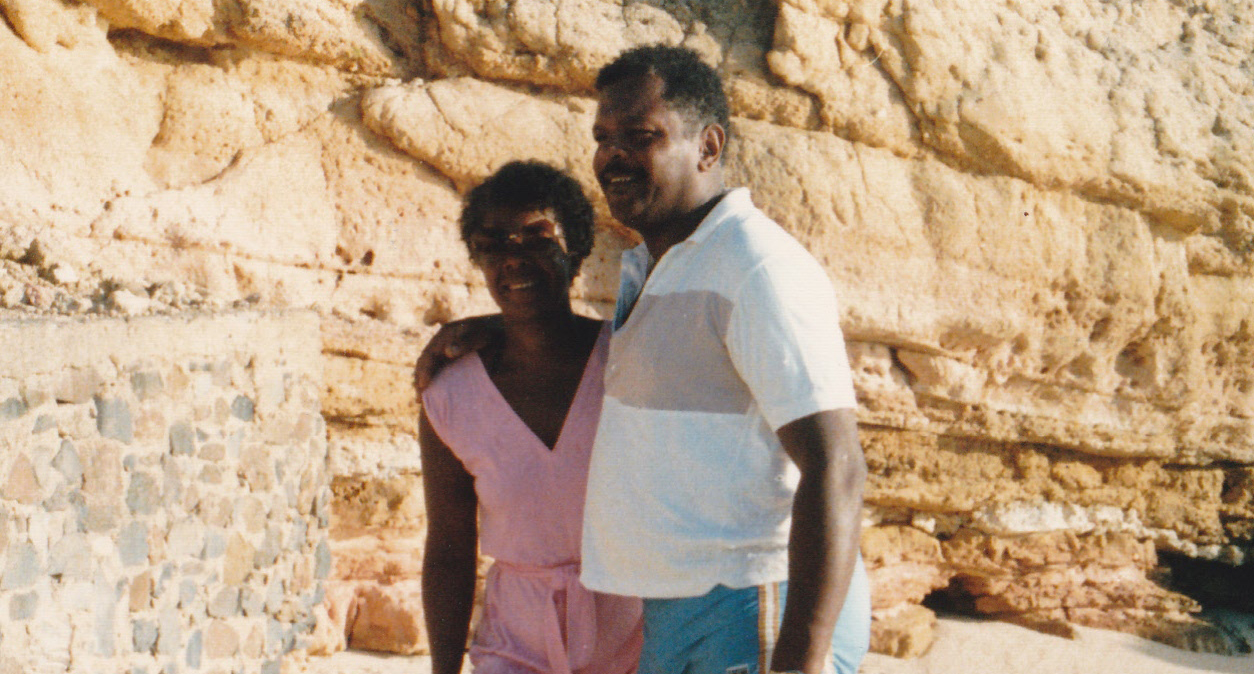

Whenever we talk about my work, she connects it with the passion my grandfather (Granddad) had for farming and fishing. Her husband for 70 years, and my father’s father, he looked at these activities not as sport or hobby, but part of life. Fresh vegetables for his family and community…sharing the bounty of a good day on the water…this made for stories and the chance to share with others, often in trade for something else. At no point did my grandfather call himself an environmentalist. However, he did know what “good” soil smelled like; that the weather in the spring would determine the harvest in the fall; and an early frost meant damage to the tomatoes, but perhaps the pumpkins and squash would be ok.

These memories celebrate my heroes. They offer me an opportunity to look back and allow me to look forward.

There is something powerful about storytelling and being able to hear about the wide range of relationships that my folks, Black folks, have had with the outdoors. From Granddad’s garden in Queens, New York to my great-grandfathers farm (on my mother’s side) in Jamaica, the relationship ranges from recreational to necessity.

My grandmother (Gran) on my mother’s side used to talk about walking to and from work and church while living in Alabama and supporting the bus boycott. She continued to walk, long after the boycott ended and she moved to NY. She would say, “When I walk, my senses are alive. You can see the crocus coming up, the dogwoods blooming, and the first signs of the leaves turning in the fall. You can smell the fresh soil in the gardens, the dew on the grass.” She also talked about the fear – her time in the country that echoed those contentious and often violent tales that are part of our history.

For my ancestors, the connection to the land, to nature was real. It was part of their lives and while there were fears, there were also joys and they wove these experiences together for me.

They would tell personal accounts of friends and family disappearing in the woods during the civil rights movement, but they could also encourage the curiosity of a six year old who wanted to take a walk amongst the trees and look for wild berries. Stares and unwelcoming behavior on walks, in playground areas and at the beach were common. What I learned from them was how to ignore that behavior, move with intention and know I had the right to be in these places. They believed that things would get better and I know their disappointment would be deep if they knew that racial discrimination in our public spaces still exists today.

I think it’s time to write a new chapter in the Black history book called “The Great Outdoors.” Let’s continue our work to make this part of the story a positive one full of healing and powerful new connections…a powerful narrative about how we were able to reclaim our relationships with nature and feel safe, supported and welcome in the outdoors.